The advocacy of women’s rights on the basis of the equality of the sexes.

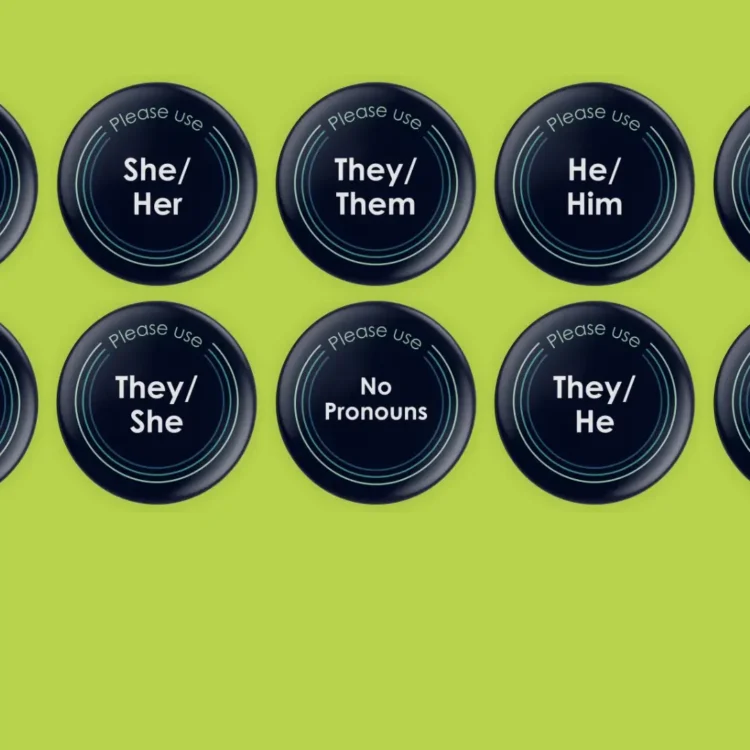

An intersectional approach to service delivery that acknowledges that the root of sexual violence is power inequality and works to reduce barriers that groups and individuals face when seeking support and volunteer or employment opportunities.